What’s new in Egypt

Is there something new being introduced in Egypt, launched by a series of mass rebellions in the country and region? If something new is being introduced, then what is it?

Change from an old structure and practice of governance to the new comes in many shades and forms. Change, even if sparked by popular uprisings, does not automatically lead to a popular government nor does it have to fundamentally overturn the power of privileged associations such as broad groups of political or military elites.

What I find significant in the transformation taking place in Egypt since the removal of Hosni Mubarak from the presidency is not the purely structural details, outlines, and schema of state and government change: i.e. political offices, which leaders among the elite are in charge, etc.

The vessel of political imagination is undergoing significant change. This is the immaterial body of the imagined community.

It is a matter of re-conceiving the essence of the state, such that the concept of community and nation takes on new meaning, that old names have new significance. This is the transformation to keep one’s eye on. It is a reframing of names and concepts, leading to a new state of governance.

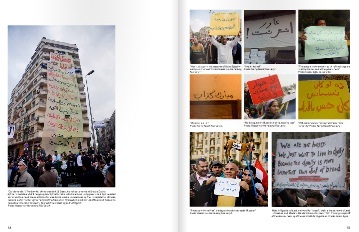

Image of Egypt's revolts from ArteEast magazine's April 2011 issue. Click on it to view the magainze in full.

In their meaning and practice, the names and categories ‘dignity’, ‘national identity’, ‘national interest’, ‘future’, ‘dream’, ‘need’, ‘government’, and ‘popular’ are undergoing investigation, and adjustment or redefinition.

The new state exists within a situation of power concentrated in the hands of associations of the elite that compose a miniscule fraction of the total population. The significant change is not one of power being shared relatively equally across a mass of people.

To put it another way, I mean that the state of affairs following the 2011 uprisings in Egypt has not led to a fundamentally emancipatory practice of social and political life. To paraphrase Peter Hallward’s philosophy on collective self-determination, the event has invented new ground but the walk through the “historical, cultural, and socioeconomic terrain” is not being organized by a deliberate assembly of the people even if they must be “conditioned by the specific strategic constraints that structure the particular situation.” (1)

There is certainly a new state of governance that is vigorously attempting to re-contextualize the concept of state and nation, but it is also clearly not a government of the people. The government of Egypt is a house of power compelled to transform itself by the sudden presence of what were established though previously suppressed incoherencies, inconsistencies, and contradictions in the old ‘regime’. This sudden presence of old contradictions appears as a great burden, a mountain of weight on the straining shoulders of Egypt.

It has come to the foreground through mass rebellion and demonstrations. It cannot be missed. It is plainly visible no matter where the gaze is fixed. The incoherencies are raw force, and they have broken the state such as it was. It is now time to grasp onto the event to organize change by transforming cultural, social, and political relationships into a new relation of thought and practice.

The associations that, until now, seem to have most successfully taken this opportunity in hand in order to forge the structure of the future Egypt, those associations that are (re)aligning the elements of the opportunity afforded them into a new state, reside predominantly within the elite, though thrust into motion by the muscle of the people. This new state is, so far, a state of the nation and not a new state of and for the people.

A tendency of privileging national identity has historically been the ease with which it is turned to the very serious zero-sum game of competing national blocs and powers. The national identity also competes with other conceptions of community and can provide “a cement which [bonds] all citizens to their state, a way to bring the nation-state directly to each citizen, and a counterweight to those who [appeal] to other loyalties over state loyalty.” (2). In this fashion, the ‘nationality’ may become “a real network of personal relations rather than a merely imaginary community.” (3) It introduces the possibility of privileging national interest by lauding those who are true defenders (patriots) of the nation tied to its instrumental apparition in the body of the state. This can endanger the effectiveness of critique as well as limit social and political options that are critical in practice.

Here is a glimpse of the tension prior to the uprisings that toppled Hosni Mubarak from nearly 30 years as president (from Amira Mittermaier’s book, Dreams That Matter: Egyptian Landscapes of the Imagination):

People can’t afford to buy anymore; the only thing left is window-shopping. We are sipping heavy tea that is bearable only with an excessive amount of sugar. But the tea is not the only thing that is heavy; so is the atmosphere. Like Ahmad, many friends during the course of my visit will explain that economically, morally, and politically, Egypt is going through a crisis. Almost everyone I talk to feels helpless, hopeless, and outraged about the ongoing war in Iraq and about the emergency laws that interdict all expressions of discontent within Egypt itself. ‘We’re living in a nightmare,’ people say when I bring up the topic of dreams.

Here’s what a Cairo taxi driver had to say, as recorded by Khaled Al Khamissi:

Education for everyone, sir, was a wonderful dream and, like many dreams, it’s gone, leaving only the illusion. On paper, education is like water and air, compulsory for everyone, but the reality is that rich people get educated and work and make money, while the poor don’t get educated and don’t get jobs and don’t earn anything. They loaf around, and I can show them to you, they can’t find anything to do, except of course the geniuses. And our boy Albert is definitely not one of those.

But I am trying with him. I pay for private lessons like a dog. What else can I do? I say maybe God will breathe life into him and he’ll turn out like Ahmed Zeweil, who won the Nobel Prize for chemistry. (4)

Another driver has this to say:

I don’t understand what they want from us. There are no jobs, then they tell us to do any job that’s going, but they’re waiting in ambush for us whatever job we do. They plunder and steal and ask for bribes and where it all leads I don’t know. Just as I spend so much a day on petrol, I have to put aside bribe money for the traffic department every day just in case. (5)

In Egypt, the practice of political power must today acknowledge the eruption of the mass response to crisis by addressing, incorporating, co-opting, redirecting, or deflecting it.

The uprisings and the resulting strain on the socio-political order were not an end to be achieved: the event is a point of departure.

The thing to keep in mind is not simply that change is taking place. It is vital to take notice of how change is taking place: what groups are and will be organizing the productions of human conditions in Egypt, and what will these conditions be? (6)

I’ll conclude with a joke as told by a Cairo taxi driver. This joke underscores the trouble with some types of change or transformation as directed by the minority who hold power. “We thank all those who voted yes in the referendum and we give special thanks to Umm Naima because she voted twice.” (7)

Sources

(1) from Hallward’s essay, The Will of the People: Notes Towards a Dialectical Voluntarism.

(2) Eric Hobsbawm, 1989. The Age of Empire, p. 149. Vintage Books.

(3) Ibid. pp. 153-154.

(4) From chapter 29 of the book, Taxi.

(5) From chapter 33 of the book, Taxi.

(6) Here, I’m adapting Peter Hallward’s some thoughts in the essay, Jacques Ranciere and the Subversion of Mastery.

(7) From chapter 33 of the book, Taxi.